paul studied but did not complete his PhD at Flinders University 1998-2001

My doctoral thesis title was,“The End of High School: A Socially Critical Hypermediated Ethnography”. It was a mouthful of a title with multiple meanings. At one and the same time, ‘the end’ referred to the final two years of compulsory education in Australia (Years 11 and 12), and posed the question of what is the ‘purpose’ and ‘goal’ of public secondary education, and its possible ‘future’. The reference to ‘socially critical’ signaled my intent to challenge power structures, inequality and injustice; ‘hypermedia’ spoke to my desire to include photography and produce a digital thesis; and ‘ethnography’ labeled my research method describing how I immersed myself in the school and the lives of students in order to understand their culture, beliefs, behaviors and experiences.

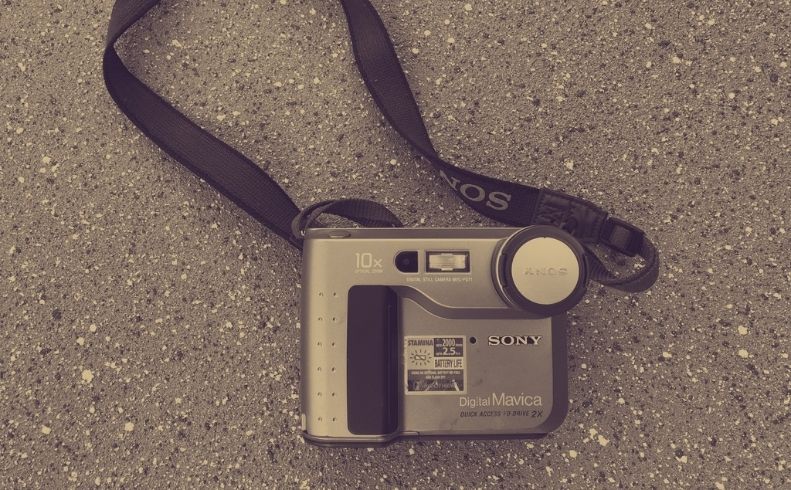

Under the supervision of Professor John Smyth (Flinders Institute for the Study of Teaching), my doctoral research focused on educational inequality and the lessons taught by the “formal” and “informal” curriculum at a public high school in a socio-economically disadvantaged suburb of Adelaide. The socially critical research project, commencing in 1998, sought to amplify the stories and ideas of young adults who had experienced adversity while at high school. The qualitative research, once completed, was to immerse readers in thick narrative description of the lived experience of a dozen young adults as they navigated the final year(s) of their formal secondary education. The work was to have invited the reader to critically consider the role of high school in the social reproduction of inequality, and the potential future role of public high schools in the production of a more just society. The research also made use of emerging digital photographic technology (this was the late 1990s) as both a method of data collection, and in the thesis presentation. Unfortunately the Faculty did not support my desire to produce a navigatable multi-media thesis (with text, digital images and embedded video on CD-ROM) and stipulated that if I wished to do that, I had to also submit my thesis in a traditional plain text format. Ultimately, in late 2001 my time ran out, my post-graduate scholarship expired, my supervisor retired, my intimate relationship ended, and I failed to submit a thesis. To this day I am deeply sorry to the participants in the study. I did not live up to my commitment to honour the stories that they so graciously shared. I have, however, never stopped trying to serve the most vulnerable in our community while, at the same time, seeking to address the structural causes of inequality. The foundation for vibrant nation and the ideas documented on this website are rooted in what I heard, what I saw, what I read, and how I grew during that period from 1998-2001

More about my PhD:

My work centred on several questions:

- What does being a young adult and attending senior high school at the close of the 20th century require, mean, and look-like? And, how does it shape their emerging identities and beliefs about society and their future?;

- What are the possibilities for young adults who will attend senior high school in the 21st century? And, what opportunities exist for the improvement of society through a transformed secondary education system?; and

- What are the opportunities, dilemmas, and consequences of critical, futures-oriented, hypermedia ethnography as a method of inquiry and (re)presentation?

For 14 months I observed and participated in the lives of young adults enrolled in a suburban high school in Adelaide at the close of the 20th century. This was a critical ethnographic study, and I was determined to amplify the voices of young adults and sociologically explore the assumptions underpinning their educational experiences. The collective stories, performance texts, and digital illustrations included in the work were an attempt to illuminate the pains, tragedies, agonies and successes of the young adults as they completed or withdrew from their final year of compulsory school. The questions asked of each participant were: who are you, what is life like for you, and are your educational experiences adequate for, or suited to, 21st century living? The short stories, or vignettes, contained in the work were open ended (this style has inspired the vibrant stories section of this website). They were written in a way that refused theoretical closure, and actively encouraged readers to gain a new insight from each reading.

Ambitiously, I had planned to connect critical sociological inquiry with evocative futures writing. In addition to the rich descriptive story writing that highlighted the lived experience of young adults, I attempted to include possible, probable, and preferred future scenarios of what high school might look like in the 21st century. The aim was to challenge readers to analyse and compare visions for the future with pre-existing arguments concerning the purpose and future of public secondary education. At no time was I seeking to predict the future, rather, I was asking readers to engage with my scenarios and imagine their own preferred future for society, and consider the role of high schools in the service and creation of a more equitable Australia as we entered the 21st century. When writing (and contrary to the advice I was given to write for the two or three academics who would ultimately grade my work) I sought to write for multiple audiences. I wrote in the hope that sociologists, futurists, researchers, policy makers, journalists, screen writers, teachers, parents, young adults, and students alike could all benefit in some way from reading the stories inside.

Additionally, I was committed to including in the work a detailed record of the way in which the ethnographic research was conducted and how the hypermedia publication was produced. My confessional account strove to demystify the research process, and make transparent the idiosyncrasies and nuances of the researcher that generally go undocumented in positivistic science research reports. I believed that, in the absence of any universal standards for the assessment of qualitative research, my tales from the field would assist readers in their evaluation of the rigor of the work. I was seeking “verisimilitude”; did it “ring true” for the reader.

After 3.5 year of intense study, I failed to submit my thesis. I had run out of time, as well as supervisorial, financial and personal resources. All was not lost, as I left with a strong, critical sociological understanding of the social reproduction of inequality. To this day I maintain the belief that schools are the last common social pathway along which all citizens travel, and that the creation of a more compassionate and committed public can begin in this publicly funded social institution. Further, some two decades later, I believe that many of our local, regional, national, and global problems could be ameliorated if we genuinely involved the emerging adult population, including kids from hard places, in the resolution of the pressing issues of our time. I still maintain that there is an urgent need to reform secondary schools as social institutions, and invent better ways to welcome young people to our world.

In the time since passed, I have not wavered in my world view that poverty, inequality, and injustice are abhorrent, and most likely preventable. I feel (and countless social indexes provide the statistical evidence), that contemporary society is unfair, unequal, and oppressive for many. Born out of my doctoral studies, vibrant nation is concerned with the pursuit of social, economic, racial and environment justice for all, not just a select few. My life time work seeks to contribute to the pursuit of a better world; a world characterised by social cohesion, ecological sustainability, and mass participation in decision making.

Favourite Quote:

“…school will endure since no one has invented a better way to introduce young people to the world of learning; [and] the public school will endure since no one has invented a better way to create a public.”

Neil Postman, 1995.